What Does It Mean to Teach the Whole Child?

A big, loaded question. A somewhat judgmental question because it infers that somewhere out there someone is only teaching parts of a child. So, needs are not being met, and that child will inevitably suffer.

Teaching the whole child means teaching more than the academic requirements. It means teaching them how to be better humans. It means teaching them about the societies they will soon navigate as adults. Teaching the whole child ensures a student has grasped the entirety of life, so they will be productive and successful in whatever they choose to do.

I have been teaching high school for the past six months. It has been one of the most thought-provoking work experiences I’ve ever had. Some of those thoughts are full of joy and excitement. I’m almost brought to tears when I read one of my students’ imaginative stories, or when they engage in a discussion on serious issues. But, other times, my thoughts are steeped in sadness and immense frustration. I teach at an inner-city public high school full of disenfranchised Black and Brown youth. I have come to understand that my purpose is to simply get them out the door and wipe my hands of them. In a heated staff meeting about our seniors, one teacher said, “They’re no longer our problem.” Sad. Frustrating. Problematic. But, honest.

For teachers, SEL is the buzzword. Social-Emotional Learning. We’re often instructed to use downtime or special days to focus on SEL; to throw a little SEL into our lessons like we’re tossing spice into a boiling stew.

Before I started teaching, I gasped at that level of honesty and often reflected on my own time in school. I thought about the bubbly, dedicated, and overworked teachers who seemed to love their jobs. I thought about my parents, and their excitement to educate every day. But that was a different time. I hate using such a cliché phrase, but it absolutely was a different time.

I graduated from high school in 1997, a whopping twenty-five years ago. How my friends and I wore revamped ’70s styles like bell bottoms and circle sunglasses, the kids today rock ’90s gear like plaid shirts and crop tops. It was also a time before cell phones, social media, and a massive mental health crisis. It was a time before schools had wellness rooms for teachers because the demand is too great. I can honestly admit that my stress level has been at its highest over these past six months.

Teachers are asked to do too much, outside of simply teaching. I have mountains of data I’m required to enter each day. I have several mandatory early morning meetings each week. There’s always some email that pops up telling me to submit this or that by some date. The emails never say, “or else,” but “or else” is implied. Most of us teach because there’s something about it that we love. But, for so many of us, this new time we exist in, has put that love in question.

Was I a problem in high school?

When I heard that teacher refer to the seniors as a problem that would happily go away soon, I again wondered about my own time in high school. Now, I went to a different type of high school. I am very aware of that. It was a magnet school, with an alternative approach to learning, and we had to take tests and interview to get in.

For the most part, we were excited to be there. And we came from these homes where we had visual representations of the power of education, of what having one could provide. Our parents had degrees and good jobs, and we lived well. So, I didn’t look at school as this horrible place I was being forced to sit in for six hours. I didn’t give my teachers the stank eye for simply doing their jobs. My students love seeing their friends, as did I, but that’s where the excitement ends for them.

I’m not a psychologist or social worker by any means, but I wonder if my students roam the halls, get in fights, and choose not to do work because they have no visual representations that make all this make sense. Sure, they see us every day and understand that we had to get degrees to teach them. But our relationships aren’t personal enough to spark a real shift. Teachers are fun snatchers. We make them do homework and take tests. There were plenty of subjects I didn’t vibe with. I don’t do math, and chemistry was a language I just couldn’t learn. But I never tied my disdain for these subjects to the people teaching them to me or to the school which required me to learn them.

My problematic behavior was occasional skipping or passing notes to my friends. Some of my students miss whole semesters on purpose. Coming to school without a notebook, pen, or pencil is a conscious decision they’ve made. And where I stepped out to take cigarette breaks, in these new times, students step out to take weed breaks, FaceTime breaks, TikTok breaks, Instagram breaks, poppin pills breaks, and detrimental breaks they are unaware will absolutely affect the rest of their lives.

This is where much of my sadness dwells. So many of my students checked out of school, checked out of life, long before high school. I’ve watched my daughter with a sharper focus in these last six months, so I can catch the moment she checks out of school, checks out of her activities, and checks out of the joy of being alive. I am, at times, brought to tears when I read background information on my students’ lives at home and the myriad domestic issues they’re experiencing.

A sad reality sets in when several of them have to leave early for work or to pick up younger siblings. Before they’ve even faced the burdens of adulthood, some of these kids have lost the joy of even being alive because of all the trauma that already comes with living. So, I try to empathize. And I think if that were me, I might be a problem too.

What does it mean to be present?

Mindfulness and presence are words that float around in the wellness space. Adults take classes and workshops on being mindful and how to improve their presence. At one point I signed up for a workshop on mindful eating because however I had been eating for almost forty years was no longer working.

For teachers, SEL is the buzzword. Social-Emotional Learning. We’re often instructed to use downtime or special days to focus on SEL; to throw a little SEL into our lessons like we’re tossing spice into a boiling stew. And I’m using that latter, flippant reference because beyond understanding the acronym I’ve never been given any guidelines or instructions on what Social-Emotional Learning is. I’m sure I could Google it, but where’s the workshop? Where’s the professional development session on SEL best practices? This would be especially helpful for new teachers like me, because I’m approaching SEL with a self-care mindset, and I’m not sure that’s the correct approach.

Nonetheless, SEL is such a huge focus because these kids have been through quite a whirlwind the past two years. Schools shut down in March 2020 and went through a rocky figuring out of the virtual learning space. Then they were virtual and hybrid for an entire year. Then they returned to school with mask mandates, Covid testing requirements, and vaccination requirements. One day their best friend is sitting next to them in class, the next day, the friend has been sent home to quarantine for ten days. And those normal school activities like the homecoming dance were out of the question.

So, teachers are tasked with talking to them about their feelings and emotions. And let me tell you, attempting to talk to teenagers about their feelings and emotions is no easy task. It’s crazy hard, and I do my best, but again, I’m not a trained professional in the feelings and emotions space. So, where is the seminar?

Today’s educators are facing a hard reality our predecessors didn’t have to. Attempting to teach against insurmountable odds, through a pandemic has shaken traditional learning so much that some new, radical, innovative approach is truly necessary.

I do understand what it means to be present, and work on my own presence daily. It takes work to be present in this world of chaos and intentional distraction. Sometimes when I’m watching the news, and there are words going across the bottom of the screen and pop-ups in the side panel, I wonder what the hell they are expecting me to pay attention to. And how am I to focus on the story the newscaster is telling me when there’s all this other stuff on the screen? That other stuff is intentional. The distractions are increasing, and the powers want us to just deal with them.

Phones are a huge distraction in school. Allowing students to use their phones defeats this hyper-focus on their feelings and emotions. The phones are the distraction in direct competition with their ability to be present. On the phone, they are having heated exchanges with boyfriends and girlfriends. On the phone, they are watching uploaded Instagram videos of recent fights in the school. On the phones, they are reading hurtful comments under their TikTok videos. But because of all the kids have experienced over the past few years, taking the phones is a delicate conversation.

But, if we’re to teach the whole child, shouldn’t we teach them how to be present? Shouldn’t we teach them that being mindful and present will contribute to their future success? There are Fortune 500 companies that have made sweeping mandates to employees that prohibit them from checking, sending, and responding to emails over the weekends. Still, schools don’t think it’s necessary to teach a child to be present. Sit on that logic for a bit.

A radical approach?

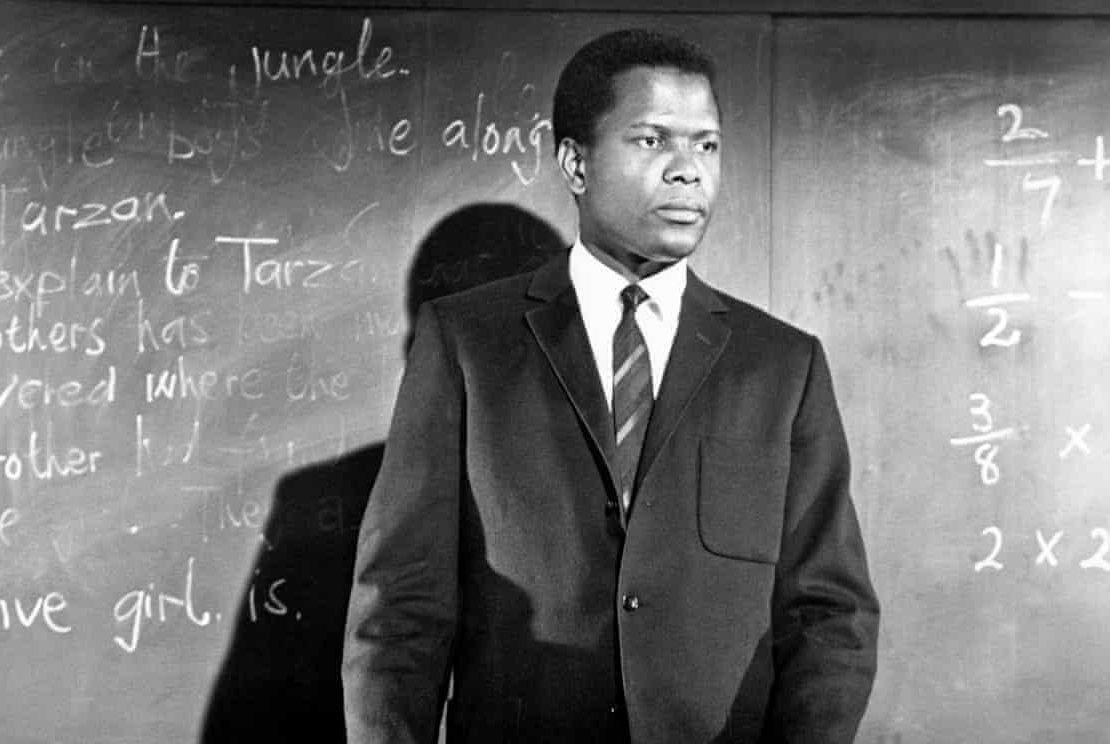

I often wonder if learning can be radical; if there are learning models that are so out-of-the-box but are highly effective. My high school, in its inception, was a very radical learning model. A school where the kids learn outside the classroom. Biology at the zoo. Instead of discussing Picasso in a book, go to a museum, look at his blue period pieces, and share your thoughts. And the actual school building didn’t include typical school spaces. We didn’t have a gym, cafeteria, or auditorium. Less places to hang out, and more reasons to get us out of the building.

When this model was designed, I wonder about the pushback, the naysayers who thought it wouldn’t work. We had a lot of freedom. There was so much freedom in this very radical approach. We ate lunch off-campus. We had to get to these classes in the city on our own. There weren’t deans and hall monitors tracking us, so we freely took coffee breaks, snack breaks, smoke breaks, or a moment of fresh air. And we always came back to school. We showed up for class. So, this radical approach worked. It didn’t work for everyone, and that’s okay. The school wasn’t intentionally exclusive. There was this humble resolve that a radical environment wasn’t for every child. In the way I don’t think my daughter would flourish in Montessori, there were students who needed a more structured approach to learning that my high school wasn’t willing to provide.

Today’s educators are facing a hard reality our predecessors didn’t have to. Attempting to teach against insurmountable odds, through a pandemic has shaken traditional learning so much that some new, radical, innovative approach is truly necessary. Whole children are not statistics. They are the sum of these magnificent parts. And they deserve an education that focuses on the entirety of their minds, lives, and well-being.